Case File

The Pergau Dam ‘Arms for Aid’ Scandal

Contents

Introduction

Introduction

contentsIn October 1993, a controversy erupted in London over whether the Thatcher government had used UK aid subsidies as a sweetener to help UK defense firms secure export orders worth more than GBP 1 billion from the Malaysian military. The subsidies in question helped finance a 600-megawatt hydroelectric dam built in the early 1990s by a consortium of UK construction firms on the Pergau River in Malaysia’s Kelantan province. While the primary focus of the controversy was on the quid pro quo of linking “arms for aid” in violation of the government’s own policies, the Pergau Dam scandal also raised questions of profiteering and bribery that were largely overshadowed.

Case Details

Case details

contentsActors

Actors

contentsMohamed Mahathir – Malaysian Prime Minister (1981-2003, 2018- ); final Malaysian decision-maker on both the Pergau Dam and arms deal.

Margaret Thatcher – UK Prime Minister (1979-1990); final UK decision-maker on the initial arms-for-aid linkage.

George Younger – UK Defence Minister (1986-1989); leading proponent of the arms deal within the UK cabinet.

A.P. Arumugam – director of GEC (Malaysia); advisor to Prime Minister Mahathir.

John Lippitt – international director at GEC; leading proponent of the Malaysian arms deal within the UK defense industry.

Allegations

Summary of Corruption Allegations

contentsA 1988 Memorandum of Understanding contained a UK government ranked list of recommended arms firms, which may have led Yarrow Shipbuilders, a subsidiary of GEC, to win the contract for frigates over Swan Hunter, a competitor which had built similar frigates for the UK government. Swan Hunter was ready to offer to build the frigates at a price of GBP 400 million, whereas the final cost to Malaysia was double that amount—a price hike which itself represents a significant corruption red flag.

Labour MP Ann Clwyd, Malaysian opposition leader Lim Kit Siang, and anti-corruption advocate Jeremy Carver have all made allegations at separate times that the Pergau Dam deal involved side-payments to Malaysian parties, either paid directly by the British construction consortium or through siphoning-off of the ODA aid package. Clwyd’s informant appears to have been an employee of Balfour Beatty, one of the British firms involved in the dam’s construction. Carver claimed that a consortium executive boasted to him of handing over a Pergau-related pay-off to a Malaysian government minister.

The Sunday Times alleged in March 1994 that many Malaysian elites had profited from the partial privatization of Tenaga Nasional Berhad (TNB), the Malaysian electricity utility. Because the size of the UK aid commitment to the Pergau project had ballooned over the course of negotiations, ODA chose to deliver its aid in the form of loan subsidies. A syndicate led by the bank J. Henry Schroder Wagg extended a GBP 306 million commercial loan for the program, while ODA offered GBP 234 million over the life of the loan to cover most of the interest. Notably, the loan was taken out by TNB, not the Malaysian government. This arrangement ran contrary to ODA’s policies that subsidized loans be borrowed by the government directly. In May 1992, the government sold a 23% stake in TNB, mostly at a fixed price, and the company listed on the stock exchange. After the first day of trading, shares gained 94% in value, eventually quadrupling in price through 1994. This suggested that the shares had been severely underpriced by TNB’s advisors—which included the same bank, J. Henry Schroder Wagg. Energy Minister Samy Vellu and other TNB executives and employees thus profited from this sale at the expense of the Malaysian and UK treasuries.

Timeline

Timeline

contents- Margaret Thatcher and Mohamed Mahathir, prime ministers of the United Kingdom and Malaysia, began to develop a positive relationship and explore potential arms and other trade deals.

- MarThe UK defence secretary, George Younger, negotiated a non-binding defense Protocol of Understanding in which he provisionally committed the government to provide non-military aid for Malaysian projects up to a value of 20% of a pending arms deal. Younger signed the protocol despite explicit prior instructions from both Thatcher and Chief Secretary to the Treasury John Major, that a defense deal should not be connected to financial support from the UK government.

- SepAlthough, the UK government attempted to de-link aid from arms by sending letters to separate Malaysian government departments at once stating that no explicit promise of aid could be included in the arms deal, and that aid would be forthcoming nonetheless, Thatcher and Mahathir signed a Memorandum of Understanding without the aid promise; nonetheless, the Malaysian side continued to act as if the aid linkage existed. To satisfy the Malaysian request for UK non-military aid, the UK’s aid agency, at that time known as the Overseas Development Administration (ODA), was pressured and rushed by government ministers into supporting the construction of the Pergau Dam. The dam, according to ODA permanent secretary Tim Lankester, was inappropriate for Malaysia’s energy market conditions.

- The release of a UK National Audit Office report and the beginning of hearings in two parliamentary committees was centered on the Thatcher (and later, Major) governments’ violation of their own policies on fire-walling aid from arms deals. A While the scandal did result in a court case, the terms of the debate were primarily political, not criminal. Nonetheless, the scandal did spawn serious allegations of corruption, most of which remain uninvestigated.

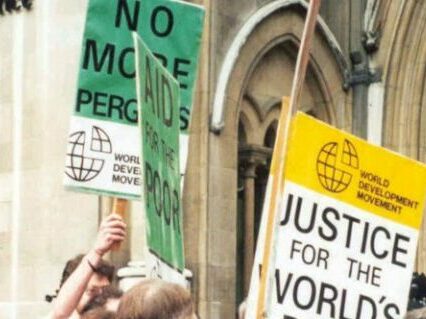

- A court case was brought by the NGO World Development Movement (WDM) against ODA, arguing that the decision to support the Pergau Dam was unlawful. The court, in a surprising decision, agreed. No bribery case was ever brought against the companies involved in the deal, likely because this form of corruption was permitted by UK law up until the adoption of a limited anti-bribery clause in 2001’s Anti-Terrorism, Crime and Security Act.

Outcomes

Investigation Outcomes

contents- In the United Kingdom, the Pergau Dam project and the “arms for aid” linkage were investigated, in turn, by the National Audit Office, the Public Accounts Committee of the House of Commons, and the Foreign Affairs Committee (FAC) of the House of Commons. The FAC was the only body which had the remit to question broader government policy and also benefitted from the revelation, on Jan. 25, 1994, of the existence of the defense Protocol of Understanding that drew an explicit link between arms and aid, later struck out in the September 1988 Memorandum of Understanding. The officials who testified before the FAC struck a common note: the arms deal would have been lost if it were not for the Pergau Dam aid promise. The FAC agreed, but criticized ministers for driving themselves into such a dead-end. The FAC also criticized the construction consortium for low-balling their initial estimate of the dam’s cost, before Thatcher made an official offer to Mahathir.

- While the Pergau Dam affair and the associated arms deal were never investigated in Malaysia, court case was brought by the NGO World Development Movement (WDM) against ODA, arguing that the decision to support the Pergau Dam was unlawful. The court, in a surprising decision, agreed. It endorsed WDM’s argument that, in complying with a Treasury rule that public expenditures be incurred with regard to “prudent and economical administration, efficiency and effectiveness,” ministers had to rely on expert opinions and not only their own good-faith best judgment in arguing that this standard had been met. No bribery case was ever brought against the companies involved in the deal, likely because this form of corruption was permitted by UK law up until the adoption of a limited anti-bribery clause in 2001’s Anti-Terrorism, Crime and Security Act.

References

References

contentsWorld Peace Foundation - Compendium of Arms Trade Corruption,

https://sites.tufts.edu/corruptarmsdeals/the-pergau-dam-arms-for-aid-scandal/

The primary source for this summary is Tim Lankester’s book, The Politics and Economics of Britain’s Foreign Aid: The Pergau Dam Affair (London: Routledge, 2013).

Doug Tsuruoka, “Rumble in the Jungle: Politics of Proposed Malaysian Dam,” Far East Economic Review, June 18, 1992, accessed through ProQuest.

Doug Tsuruoka, “Counting the Costs: British Report Probes Aid for Malaysian Dam,” Far East Economic Review, Dec. 16, 1993, accessed through ProQuest.

Stephen Bates, “Hurd to Face MPs Over Ministers’ Roles in Dam Deal,” The Guardian, Feb. 12, 1994, accessed through LexisNexis.